Top Nine DC Sights

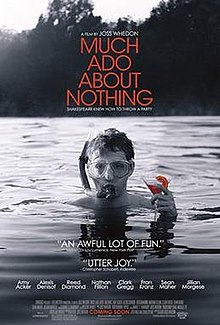

Ok, it seems a shame to sign off with the rather rushed review of the

Free For All Much Ado About Nothing

(excellent though it was), so here is my final post on DC, written in the

comfort of my living room in England. This final list of DC sights includes

those that were not covered in my other reviews or, mostly, covered in the post

on the sights explored when my family visited.

1) The Library of Congress – this has already been mentioned in my ‘family sights’ post, but it gets in

twice because I’ve been working there, and it really does have some great

artefacts that I didn’t mention before. Even beyond the great works from

America’s earliest days, the Library also displays some incredibly important global

books – like the Gutenberg Bible, the first great book to be printed, which

sits in the Great Hall opposite the Giant Bible of Mainz, the last of the great

handwritten books from the days before printing. And the Jefferson Building

itself is impressive. The Great Hall and the Main Reading Room are worth a trip

in themselves.

2) The National Gallery is another wonderful

building. The neo-classical architecture can get a bit same-y but the East

Building is a modernist marvel, and the interiors of both are perfect,

especially the in-door seating/arboretum areas upstairs in the West Building.

Art-wise, the dearth of Georges Braque works was a little disappointing but it

was made up for by the El Grecos – these really are dazzling. I was walking

past their room when I caught a glimpse and then I had to examine them.

Hundreds of years ahead of their time, these were the highlight of my visit.

3) The Phillips Collection. A special Braque still

life exhibit was on during my visit, which was beautiful. A lot of cubism can

be quite depressing, but these works from the late 20s to the 40s manage to be both profound and uplifting. There is also another wonderful El Greco here too. The

building was clearly grand as a house but as a gallery it feels almost intimate

compared to the National. Well worth a visit.

4) Arlington Cemetery - I didn’t get to find the grave of Orde

Wingate (the man who created the Chindits and led my granddad against the

Japanese in Burma in WW2) who is buried there, but a moving trip nonetheless.

5) Ford’s Theatre (where Abraham Lincoln was shot)

– great after hours tour by Charlotte Reineck – it’s not a period of history I

know much about (and Abraham Lincoln:

Vampire Hunter isn’t as much use as you might wish), but this tour was

informative enough that I came away knowing a lot more about it, but

entertaining enough that I didn’t feel overwhelmed with facts.

6) Baseball games at the Nationals Park. The really

weird thing here, which you would never guess from the mobs of devoted fans

attending on a Friday evening, is that DC has only had its own Major League Baseball

team for a few years. Before 2005, most Washington residents supported the

Baltimore Orioles (and many apparently still do). For somebody, like me, who watches

his local cricket team struggle to get a few hundred spectators turn up for a

first class match, the fact that so many Americans can get so excited so often

(they have around 80 home games a season!) is truly impressive. I watched a

mere three of their home games, but each one was lots of fun, although I’m

still a little dubious about the nutritional value of the Half Smoke.

6) Baseball games at the Nationals Park. The really

weird thing here, which you would never guess from the mobs of devoted fans

attending on a Friday evening, is that DC has only had its own Major League Baseball

team for a few years. Before 2005, most Washington residents supported the

Baltimore Orioles (and many apparently still do). For somebody, like me, who watches

his local cricket team struggle to get a few hundred spectators turn up for a

first class match, the fact that so many Americans can get so excited so often

(they have around 80 home games a season!) is truly impressive. I watched a

mere three of their home games, but each one was lots of fun, although I’m

still a little dubious about the nutritional value of the Half Smoke.

7) Freer Gallery – Asian art is not normally my

thing, but this place has such an excellent collection, it is so stylishly laid

out and it is such a calm

and cool pool of tranquillity on a hot DC day, that

you cannot help but fall for the pieces on display. The inclusion of western

artworks inspired by Asian artefacts, like Whistler's Asian influenced scenes of London, was also

surprisingly successful. And these beautiful Chinese jade artefacts from the neolithic period were new to

me.

8) Dumbarton Oaks. This is definitely worth a visit

whether you enjoy beautiful old houses, delightfully peaceful and charming

English-style country gardens, or wonderfully idiosyncratic museums (a museum

focusing only on pre-Columbian American art and Byzantine art doesn’t sound

like it would work, but it really does). And it’s in Georgetown, so you can

check out one of DCs best areas for shops, bars and restaurants too.

9) Great places for a drink that really should have

appeared in House of Cards. The Capitol Hill Club (you’ll need a member to

accompany you inside), the Old Ebbitt Grill, and the Teddy and the Bully. Teddy

Roosevelt plays a prominent role in the latter two establishments (and there is

at least one painting of him in the Capitol Hill Club), including the heads of

a bunch of animals he shot in the Old Ebbitt Grill (which makes it sound worse

than it is).

So that’s it for my trip to Washington, DC. It hasn’t transformed me

into a Renaissance Gentleman, as I had hoped it would, but it’s been a lot of

fun and it’s kindled an interest in theatre which I hope to maintain (my first

trip to Stratford upon Avon to see some Shakespeare is already booked). As big

cities go, Washington is one of the best.